I’ve been thinking about something you said: “Islam began as something strange and it will go back to being strange, so give greetings to the strangers.”

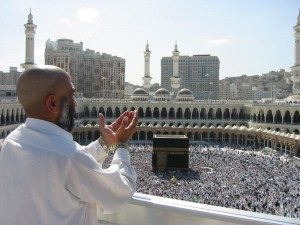

To try to understand this for myself, I’m imagining the time before you became The Messenger. When you were still just an ordinary resident of Mecca, the sanctuary around the Kaaba was full of idols. I can visualize this by remembering the temples and shrines I saw in India. Some idols would be figures with a human likeness, heaped with jewelry and wafted with incense, while others would be squat mounds smeared with butter or milk or blood-red vermilion.

You’d watch the pagan pilgrims bowing down, laying gifts of gold and silver at the base of these statues. You’d see them sighing and murmuring prayers, sifting the sand of the shrine through their fingers into little leather bags they would then hang around their necks as amulets.

You’d also observe the Christian pilgrims coming to worship Jesus and Mary: lighting candles in front of their painted images, the priests rubbing oil onto their foreheads.

You’d watch all of this with curiosity, not judgment. Because you were sensitive, and because the veil between the Seen and the Unseen would be especially thin in a place like Mecca, you would know that there are many orders of beings, and many kinds of energies that human beings can contact. You’d understand how this kind of error could be made. Especially because humans have weaknesses, chief among them being lazy. We want shortcuts, get-rich schemes, someone to do the hard work for us.

It would have been the same with the Meccan traders, the merchants and financiers. Smooth-talking, complacent types, certain the money they served would take care of them. When they weren’t making deals they’d be thinking about them, and to celebrate their success they’d throw huge parties and get drunk with the pretty women or handsome boys they kept in their pleasure-palaces. Also: they’d spend a lot of time admiring themselves in the mirror.

You were not like that. You were so plainly uninterested in money that people would give you their valuables for safekeeping when they left town. You were known as the trustworthy one, “al Amin.” Maybe it made you seem odd, or even a bit slow. I can imagine people thinking that, with your smile and easy manner. No doubt some took advantage of your trust.

The Mecca of your time was not an enlightened society. When Jaffar Ibn Abu Talib sought asylum from the king of Abyssinia with some of the early Muslims, he explained what life was like before the revelation:

We were a people lost in ignorance. We worshipped idols, we back-stabbed one another in gossip, we committed sins without shame, we severed the bonds of mercy among us, and we were unkind neighbors. The strong among us devoured the weak.

That description of the time of ignorance, the jahiliyya, could apply just as well to my own society, only in the present tense. Ignorance sets the standard for our politics, for our economics and for our entertainment.

In my mind, that is the most convincing explanation for why Islam is perceived as such a threat to the West. It proposes unity as the basis of reality, and coherence for the human being instead of fragmentation. It asks us not to be wasteful or greedy. And it puts us in a universe governed by spiritual law, whose workings can be grasped by reason as much as the imagination. For me Islam has been the opposite of a doctrine of blind faith. From the beginning, it has been a path of gaining knowledge through experience; asking questions and exploring for myself every step of the way.

Have I told you my conversion story? It was like being washed ashore after a shipwreck: in this case, 9/11. After it happened, all the pieces of normal New York came apart and started floating. One of the images that has stayed with me from that time is of two people on bicycles, pedaling leisurely down the middle of Broadway. No taxis, no livery SUVs with tinted windows, no delivery trucks, no bike messengers. The streets were empty. There was such a feeling of openness. The usual rules and routines were suspended. You couldn’t go to work. You couldn’t even get money out of the ATMs for a while.

A lot of people went to the parks or botanical gardens. I sought out books. Though I couldn’t have said quite why, the stories on the news didn’t ring true to me. So I went to the big library in Midtown and started to explore the 965-number stacks, where Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Middle East were all located. I wanted to understand for myself what had happened, and why. I read everything I could get my hands on for the better part of a year. In the process, I gained some context and background knowledge, but felt I was still lacking a sense of clarity.

Then something happened in parallel that I wasn’t expecting. It didn’t have anything to do with reading or thinking. It was a new perception. With all the images of Muslims suddenly in the media, I started to notice a quality of light radiating from some of their faces. I didn’t have the word nur for it then, and I also didn’t know it was one of your distinguishing features. But I could perceive it.

From my perspective now, I would say that a veil had been lifted. I thought I was searching for the truth of facts, but truth of a higher order was revealed.

That was how I began my journey toward Islam, a journey that feels more and more like I am leaving a place where I had been a stranger for so long, and am finally coming home.

Holding your hand as we approach the city gates,

Anna

Photo by Ali Mansuri, via Wikimedia Commons

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (1 of 11)

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (2 of 11)

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (3 of 11)

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (4 of 11)

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (5 of 11)

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (6 of 11)

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (7 of 11)

Read Love Letters to Muhammad (8 of 11)